Requests for Comments

By stretch | Monday, December 1, 2008 at 12:44 a.m. UTC

When reading about network protocols, one will inevitably encounter references to various RFCs. Not many people take the time to actually follow up on these references, which is unfortunate because familiarizing yourself with an RFC can yield huge advantages when designing a complex network or when charged to troubleshoot particularly obscure predicaments.

An RFC, or Request For Comment, is a memorandum written by one or more network engineers and published by the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) to propose new standards or to convey new ideas. "Request for comment" may seem like a bit of a misnomer as many RFCs end up as de facto Internet law, but the term originates from each document's initial function as a solicitation for peer review. There are four categories of RFC:

- Standard (STD), Draft Standard, or Proposed Standard - Official protocol specifications

- Best Current Practice (BCP) - Official guidelines and recommendations

- Informational (FYI) or Experimental

- Historic

An RFC begins the publication process as an Internet draft, which undergoes a cycle of editing and review. Anyone can submit an informational or experimental Internet draft for review, but standards track and BCP submissions must come from an IETF working group. A lengthy review process is necessary as RFCs, once published, are never modified; minor errors are listed as separate errata, while significant revisions require the submission of a new draft.

Each RFC is assigned a serial number by the RFC editor, in loose chronological order (RFCs don't usually appear in perfect sequence due to the varying lengths of each review). The entire review process itself is published in detail, appropriately enough, in RFC 2026.

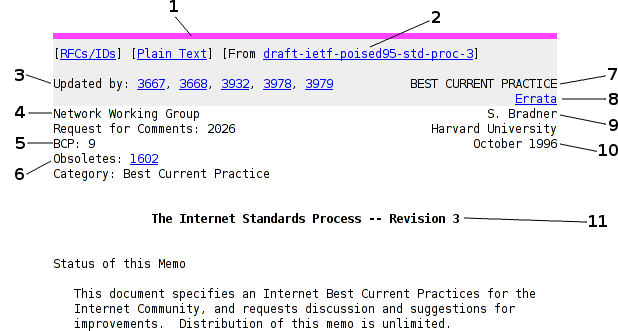

Published RFCs can be found at a number of places, but my favorite is the IETF tools website. Here each RFC is formatted with a meta header (the section with the grey background) containing helpful additional information:

- Color bar indicates status

- Original Internet draft

- Updates to this RFC since its publication

- IETF working group

- Series number

- Previous RFCs made obsolete and/or updated by this one

- Status

- Errata listing

- Author(s)

- Date

- Title

Most modern RFCs begin with a status declaration, an abstract statement of purpose, and a table of contents. The TOC itemizes the contents of the RFC by section and page just like a book, so that you can easily navigate to a particular topic if you're looking for specific details. Many RFCs include additional references and one or more appendices at the end.

Many people will find the pages of plain black and white text daunting, but reading an RFC from start to finish isn't as dry as you might think. RFCs are written by engineers, for engineers, and are typically worded very efficiently. Additionally, remember that RFCs are formatted in fixed-width plain text; each page is significantly less dense than an average book, and consequently reads much quicker.

Posted in Resources

Comments

December 1, 2008 at 9:08 p.m. UTC

Congratulation. Very good post.

December 2, 2008 at 5:27 p.m. UTC

Excellent post. This will motivate some of us to actually go and read RFCs.